Slaughter & Rees Report: Happy Fiscal New Year. And a Stormy One, Too.

"Fiscal 2018 was in many ways a disaster for the fiscal health of America—today and in the future," say Slaughter and Rees.

Perhaps the only area of bipartisan agreement today is on ignoring conversations about fiscal austerity. | iStock: pabradyphoto

Here in the United States, October 1 marks an important day for public policy, as it always does: the start of the federal government’s new fiscal year.

That is a good thing, because fiscal 2018 was in many ways a disaster for the fiscal health of America—today and in the future.

America’s economy in 2018 has been very close to, if not at or slightly over, full employment. In July the unemployment rate was just 3.9 percent, and the over 6.9 million job openings in the U.S. labor market that month exceeded the country’s 6.3 million unemployed people. Annualized growth in gross domestic product (GDP) hit 4.2 percent in the second quarter, a rate widely thought to be faster than the sustainable long-run potential.

There once was a time in U.S. fiscal history when such cyclical strength would have yielded a fiscal surplus, thanks to some combination of sufficiently strong tax revenues and a slowing in automatic-stabilizer spending, such as unemployment insurance. Indeed, the last time U.S. unemployment fell below 4 percent was in 2000, the fourth year in a row that the federal budget came in as a surplus.

No longer. Through the first 11 months of fiscal 2018, America ran a fiscal deficit of $895 billion. The full-year deficit may well have hit $1 trillion, about 4.2 percent of GDP—in contrast to just 2.5 percent in 2015. Part of what drove this yawning deficit was last year’s cut in personal and corporate tax rates under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The other part was the bipartisan relaxation of spending caps that prompted growth in both military and domestic spending.

Is there any prospect for greater fiscal restraint in this new fiscal year? We wish. Few citizens seem to care about these deficits. An April Kaiser Health Tracking Poll found that just 14 percent of Americans cited the deficit as the country’s most important issue. And perhaps the only area of bipartisan agreement in Washington today is on ignoring any conversations about fiscal austerity. Indeed, House Republicans in recent weeks have been pushing to make permanent the cuts in personal tax rates passed last year that are due to expire in a few years, while many Democrats have been advocating for substantial expansions to Medicare and Medicaid. Retired Senator Kent Conrad, a Democrat from North Dakota, was recently quoted lamenting this situation. “It’s not just irresponsible, it’s wildly irresponsible. If you are seeking elective office, the hardest thing in the world is to say, ‘I’m going to raise your taxes or cut spending on popular programs.’”

All of this current fiscal profligacy comes in an environment that former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke once labeled, “the calm before the storm.” In June the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office issued its annual publication that looks out 30 years, The Long-Term Budget Outlook, and this latest installment is best read sitting down with a warm glass of milk or some other such soothing beverage. Here is how this report opens.

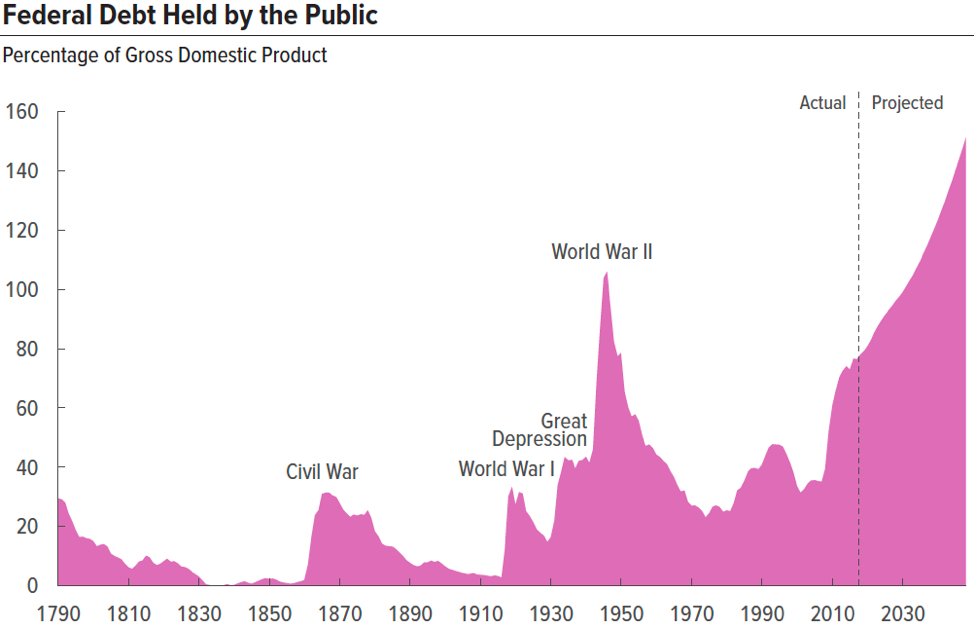

In CBO’s projections, the federal budget deficit, relative to the size of the economy, grows substantially over the next several years, stabilizes for a few years, and then grows again over the rest of the 30-year period, leading to federal debt held by the public that would approach 100 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) by the end of the next decade and 152 percent by 2048. Moreover, if lawmakers changed current laws to maintain certain policies now in place—preventing a significant increase in individual income taxes in 2026, for example—the result would be even larger increases in debt.

What the euphemistic adverb “substantially” means in numbers is that annual fiscal deficits are projected to steadily expand, from this year’s of about 4.2 percent of GDP to a projected average of 4.9 percent in the 2020s, 6.1 percent in the 2030s, and 8.4 percent in the 2040s. Driving this steady expansion will be spending increases, rather than revenue declines. An aging U.S. population will drive up federal spending on Social Security and, even more because of ongoing increases in health care costs, Medicare and Medicaid. On top of all this, interest payments on outstanding debt will climb—both because of the rising overall debt and because borrowing costs are forecast to be higher than recent record-low levels.

As the following LTBO figure shows, this projected escalation of fiscal indebtedness starts from a current situation where total U.S. fiscal debt as a share of GDP—currently at about 78 percent—has never been this high, except for a few years in and around World War II. It also assumes a next 30 years free from financial crises, depressions, and wars—the shocks that have traditionally driven spikes in fiscal indebtedness. We say this not hoping for such tragic calamities, but simply to point out that this stormy fiscal future is gathering mainly because of demographics.

And, we feel compelled to note, all of these CBO forecasts assume that current tax and spending laws play out as currently written. In a companion study to its LTBO, CBO redid its analysis under the alternative future where the spending increases and tax cuts of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act are made permanent—per what many in Congress are already advocating—rather than expiring in the next several years as the legislation stated. In this alternative-yet-perhaps-likely future, deficits and debt rise much more dramatically. By 2038 the fiscal deficit would hit 10.5 percent rather than 7.1 percent, which would be the highest since World War II, and by 2048 debt would have risen to not 152 percent but rather about 210 percent.

What could clear all these clouds? Some combination of three things: a sustained acceleration in aggregate productivity growth for America, which would yield faster growth in tax revenues; a substantial expansion in immigration, which thanks to a larger labor force would similarly expand revenues; or a sustained acceleration in productivity growth in health care, which would slow the growth of Medicare and Medicaid spending. Growth in health care costs has slowed in recent years, but for decades they have outpaced general price inflation—and are forecast to continue to do so, even if at rates slower than in the past. A sustained productivity boom would be wonderful but, as we have written here, does not seem to be materializing. And the odds for more-liberal immigration policy don’t seem to be all that high when what limited conversation there is in Washington about immigration focuses on walls, not bridges.

Perhaps the most sobering aspect of America’s gathering fiscal storm is how it is revealing a deep societal preference for protecting the old over investing in the young. In 1968 all federal spending excluding Social Security, the major health programs, and interest was 15.3 percent—a time of high national investment in basic science and research, highlighted then by that NASA program that was about to put Neil Armstrong on the moon. That number had fallen to 11.4 percent by 1988 and about 9.0 percent this year—and is projected to fall to just 7.6 percent by 2048. In 2017 the federal government spent $939 billion on Social Security, $591 billion on Medicare, and $375 billion on Medicaid. And the Department of Education 2017 budget, you ask? About $68 billion.

Happy fiscal new year.