Truth and Rumors

B. Espen Eckbo examines share price run-ups in merger negotiations and finds that neither side puts much stock into the rumors.

Imagine you've spent two months negotiating a merger agreement with a target firm. The deal is ready to be signed and announced to the public the following day. Based on the target's secondary market price of $12, observed at the start of the merger negotiations, you propose a takeover price of $18 per target share. This represents an increase of VP = $6 per share over the target's secondary market price of $12, a premium of 50 percent. Both parties have indicated that such a premium is reasonable for this type of target firm and industry.

Just before signing the agreement, however, the target notes that its stock price has increased significantly over the past two months. The target market price is now $14, a run-up of VR = $2 from its previously assumed stand-alone value of $12. You have not been buying the target company's stock in the market nor is there any reliable public evidence to show who has. So do you go forward with the $18 offer or do you raise it, perhaps to $20?

Your answer depends on whether you believe the $2 target run-up represents an increase in the firm's stand-alone value—that is, a permanent increase independent of the merger. Positive events, for example, may have caused a general revaluation of firms throughout the target industry during your merger negotiations. In this scenario, raising the bid to $20 would be just fine with the bidder because it would not reduce the bidder's synergy gains from the deal.

But what if the target-price increase is the result of deal anticipation triggered by rumors of merger negotiations? Such rumors cause investors to build the expected value of the offer premium into the current price. In this scenario, the target market price now consists of the $12 stand-alone value plus an expected offer premium of $2. Raising the offer price to $20 is now costly for the bidder. It means that the extra $2 is literally paid twice to the target. The target, of course, subscribes to the stand-alone-value scenario and demands that you raise your offer price. Since neither party knows the true source of the run-up, what do you do?

While the leading research paper in the area, published in a top academic journal in 1996, claims that run-ups do indeed result in offer price markups, Tuck professor B. Espen Eckbo was not convinced. "We were puzzled by the earlier research conclusion because takeover-bid announcements are often preceded by market rumors and ‘street talk,' which themselves lead to speculative target-price increases," says Eckbo, Tuck Centennial Professor of Finance and founding faculty director of Tuck's Lindenauer Center for Corporate Governance. "Given the rumors, why would bidders agree to raise the offer price by the run-up? We set out to examine this puzzle, and our research in fact reverses the earlier conclusion."

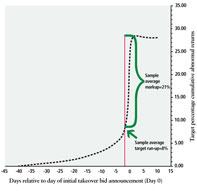

To see why, consider figure 1, which shows what happens on average to the market prices of publicly traded targets from two months before through 10 days after the first public announcement of the merger deal (which occurs on Day 0). The figure, which is based on a total sample of 6,150 public targets from 1980 to 2010, shows an average percentage target-price increase over the two months leading up to and including the initial offer announcement of VP = 29%.

Moreover, the average preannouncement run-up is VR = 8%. That means the average offer-price markup on top of the run-up is VP – VR = 21%. Recall that earlier, if the parties were to agree that the run-up represents an increase in the target's stand-alone value, the markup will increase from $6 to $8. However, if the parties agree that the run-up simply reflects rumor-induced anticipation of the deal by the market, the offer premium remains unchanged at $18 and the markup drops by $2, from $6 to $4. This suggests that solving the markup-pricing puzzle requires finding out how markups covary with run-ups in the cross-section of takeover bids.

Eckbo and his coauthors attacked this issue by first developing a precise mathematical model for how market prices ought to rationally respond to rumors of a pending takeover. Their general pricing model, when bidders do not mark up the offer price with the target run-up, has the following simple equation (click images to view full size):

Figure 1

|

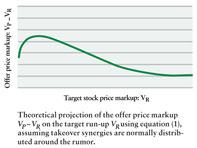

Figure 2

|

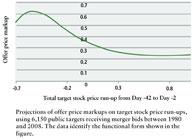

Figure 3

|

Here, π is the rumor-induced probability that a deal will take place. As you can see, the markup VP – VR is highly nonlinear in the run-up VR, a new discovery in the finance literature. "When we took this model to the data, the empirical results were striking," says Eckbo.

Figure 2 offers another view of the theoretical projection in the above equation (1), where the horizontal axis is the target run-up VR and the vertical axis is the offer price markup VP – VR. Figure 3 shows the result of an unconstrained estimation of equation (1) using the 6,150 observations on run-ups and markups underlying figure 1. The similarity between the theoretical function in figure 2 and its empirical counterpart in figure 3 is visually dramatic and supported by a battery of statistical tests.

In the end, it appears that parties involved in merger negotiations treat target run-ups as phenomena caused by deal anticipation and do not find it necessary to adjust the offer price. "For the first time, bidders now have access to systematic empirical evidence to counter opportunistic target claims that target run-ups should be matched by offer-price markups," says Eckbo.

BE Eckbo, S Betton, R Thompson, KS Thorburn, 2011, "Merger Negotiations with Stock Market Feedback," Tuck School of Business Working Paper 2011–94

Sandra Betton is associate professor of finance at the John Molson School of Business at Concordia University in Montreal. Rex Thompson is professor of finance at the Cox School of Business at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. Karin S. Thorburn is Research Chair Professor of Finance at the Norwegian School of Economics in Bergen.